Digital accessibility, inclusive human-centred design, and why it matters

Introduction

Accessibility is an incredibly important, yet critically often overlooked, aspect of digital user experience. As individuals, it’s easy to use our own abilities as a baseline and evaluate digital products based on our own bias. Because of this, our products may be easy to use for people who are like us, but may exclude others.

This problem persists both inside the technology industry (at a supplier level) and also in the global marketplace at large. Tota11y estimates that over 95% of developers have had no accessibility training and did not learn it as part of training to be an engineer.

Accessibility needs advocates and allies at all levels of business to ensure that it is understood as a core business requirement, without exception. Accessibility is most commonly sidelined due to a fundamental misunderstanding of its meaning and benefits, alongside a plethora of common business case excuses predicated on misconceptions.

Contents: accessibility misconception bingo

- “We don’t have the budget for accessibility”

- “It’s not a business priority at the moment”

- “None of our users are disabled”

- “Disabled users already have tools for this stuff”

- “The requirements keep changing and we can’t keep up”

- “Accessibility will compromise our website design or branding”

- “Nobody else does it so why should we”

- “It’s someone else’s responsibility”

- “Compliance is too difficult to achieve”

- “It’ll require a rebuild”

- “There’s no legal requirement for us to do this”

- “We don’t want to affect the UX for the majority of our users”

- “We can use an overlay service to be compliant with low effort”

- “There’s no benefit to us doing this”

- “We don’t know how or where to start”

“An estimated 1.3 billion people – or 16% of the global population – experience a significant disability today. This number is growing because of an increase in noncommunicable diseases and people living longer.”

World Health Organisation – " decoding="async" >

World Health Organisation – " decoding="async" > The business case

Inevitably, what may prove to be the strongest motivating factor for businesses seeking to make their digital products accessible is the compelling financial impetus. From a business perspective the cost of inaccessibility can cause irreparable damage to a brand.

Whilst accessibility may seem like an additional cost constraint the results benefit both businesses, in terms of return on investment (ROI), and a larger number of people who can use products or services.

The best way to present this argument is with cold hard statistics:

1 6 m

There are over 16 million disabled people in the UK, that’s approximately 1 in 4 – Scope

£ 1 5 . 1 bn

Disabled online shoppers, who click away from inaccessible websites, had a combined spending power of £17.1 billion in 2019 – The Purple Pound

8 %

80% of customers with impairments spend their money where they have the easiest digital experience – Click-Away Pound Survey 2016

7 3 %

73% of potential disabled customers experience barriers on more than ¼ websites they visited – Click-Away Pound Survey 2016

2 4 . 6 %

The UK population is ageing, it’s estimate that 24.6% will be 65+ by 2050 which equates to more users relying on accessibility – The Telegraph

× 3

The proportion of adults aged 65+ who shop online has trebled since 2008, rising from 16% to 48% in 2018 – Office for National Statistics

Not only this, but there are many other key areas of digital product improvement which overlap with accessibility standards. Site speed (Performance), SEO ranking, UX and conversion rates all increase in direct correlation with accessibility.

“The global market of people with disabilities is over 1 billion people with a spending power of more than $6 trillion.”

The Web Accessibility Initiative – " decoding="async" >

The Web Accessibility Initiative – " decoding="async" > Litigation, legislation and regulation

Digital accessibility and inclusion is quickly becoming a priority for many organisations in both the public and private sectors.

- In the UK more stringent legislative regulations connected to the Equality Act 2010 have been a driving force for improvements, particularly in the public sector.

- While in the US a boom in ADA (Americans with Disabilities Act) lawsuits, and continuing upward trend of litigation, has been a direct force for change. This includes high profile legal cases against household names such as Netflix and Domino’s.

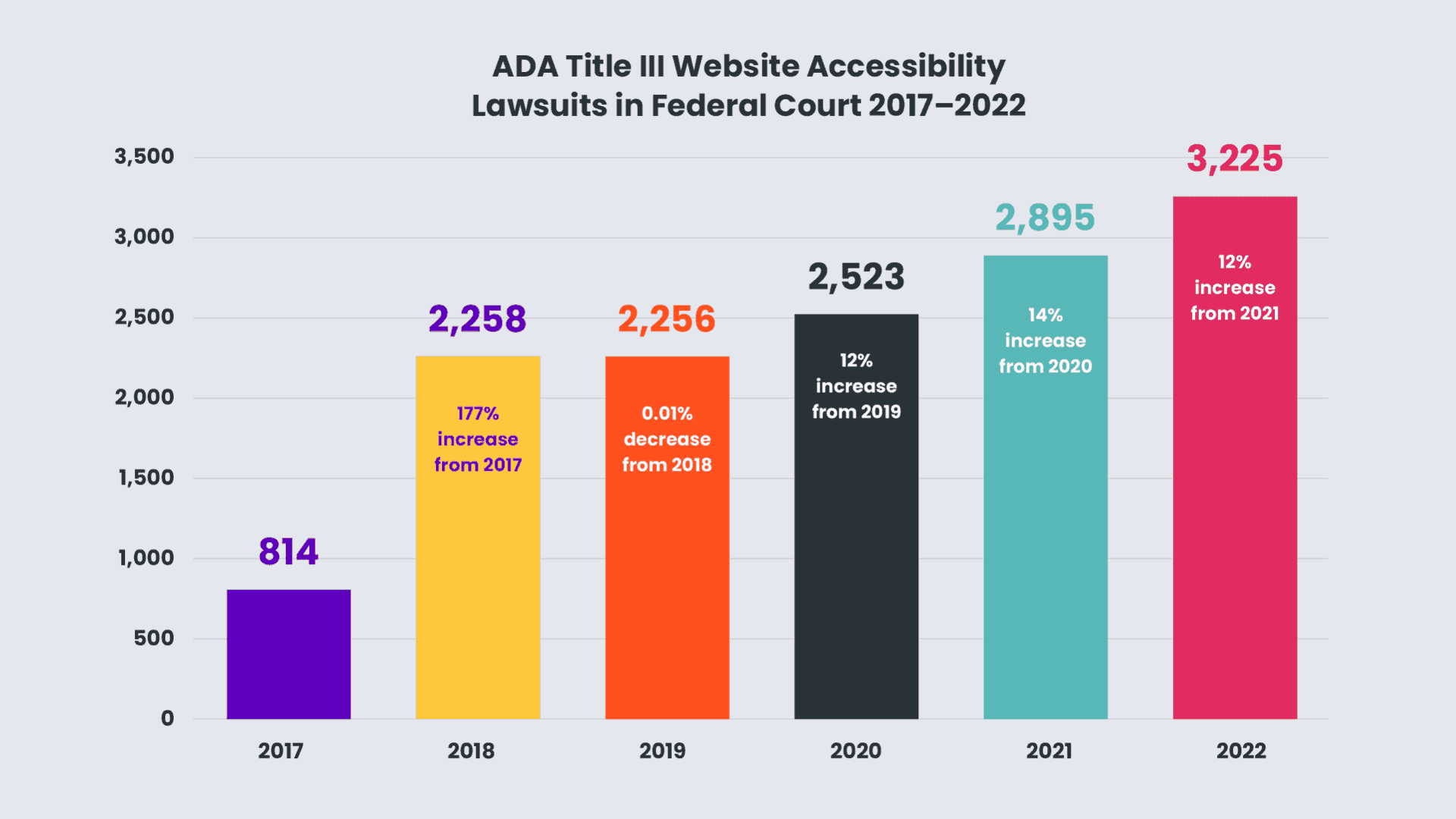

Caption: ADA Title III Website Accessibility Lawsuits in Federal Court 2017-2022.

2017 (814), 2018 (2,258, 177% increase from 2017), 2019 (2,256, 0.01% decrease from 2018), 2020 (2,523, 12% increase from 2019), 2021 (2,895, 14% increase from 2020), 2022 (3,225, 12% increase from 2021).

At the time of writing, there is no legal precedent for accessibility lawsuit enforcement in the UK. Only a handful of companies have faced legal action brought by The Royal National Institute for the Blind (RNIB), but these cases reached a settlement before being heard by a court.

That’s not to say that digital accessibility shouldn’t be of growing concern to UK organisations and that we shouldn’t expect to see a similar pattern of legal action here.

So what are the legal requirements to making a website accessible?

-

The UK commercial sector

The accessibility of websites in the UK commercial sector is covered, as previously mentioned, by the Equality Act 2010. On 1st October 2010 the Disability Discrimination Act 1995 (DDA), along with a range of other discrimination laws, was replaced by the Equality Act 2010 in England, Wales and Scotland (in Northern Ireland the DDA is still the law).

The Equality Act covers all the provisions in the Disability Discrimination Act as well as some additional protection from indirect discrimination, discrimination arising from disability and discrimination on the basis of association or perception. The DDA states that it is unlawful for “a provider of services” to discriminate against a disabled person.

The Equality Act 2010 protects individuals from discrimination and advances equality of opportunity on the grounds of nine protected characteristics, of which disability is one. This Act requires digital product owners to make ‘reasonable adjustments’ to their products to anticipate the needs of potential disabled customers/users.

The ISO 30071-1 digital accessibility standard, released May 2019, is an international process-orientated code of practice enabling organisations to embed accessibility in their “business as usual” processes.

It extends to cover:

- Websites

- Email clients

- Virtual learning environments

- SaaS (Software as a Service)

- RIA (Rich Internet Applications)

Recommendations state that organisations should:

- Consider accessibility in decision-making processes throughout the development phase of any website in accordance with WCAG standards.

- Have an established policy for digital accessibility, and document any decisions related to digital accessibility.

- Communicate accessibility decisions and goals clearly by publishing an accessibility statement on their website (more on this later).

-

The UK public sector

Digital accessibility in the public sector is of even greater importance because users may not have a choice when using public sector digital services, so it’s important that they work for everyone.

Similarly to the private sector the public sector is governed by the Equality Act 2010, but the requirements are more stringent.

Accessibility regulations (Public Sector Bodies (Websites and Mobile Applications) (No. 2) Accessibility Regulations 2018) came into force for public sector bodies on 23 September 2018 stating that in order to meet the legal requirements all UK public service providers must:

- Make their website or mobile app compliant to WCAG accessibility standards

- Publish an accessibility statement on their website

- Include disabled users in user research

- Test with common assistive technologies

The only argument for partial exemption from complying with these regulations is if it presents a ‘disproportionate burden’ to the organisation. This is the case if the impact of fully meeting the requirements is too much for an organisation to reasonably cope with, but the organisation would need to undertake a formal assessment to make this case.

The Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) in England, Scotland and Wales and the Equality Commission for Northern Ireland (ECNI) in Northern Ireland will enforce the requirement to make public sector websites and mobile apps accessible.

Organisations that do not meet the accessibility requirement or fail to provide a satisfactory response to a request to produce information in an accessible format, will be failing to make ‘reasonable adjustments’.

This means they will be in breach of the Equality Act 2010 and the Disability Discrimination Act 1995. The EHRC and ECNI can therefore use their legal powers against offending organisations, including investigations, unlawful act notices and court action.

More information can be found on UK public sector legal requirements on the GOV UK website.

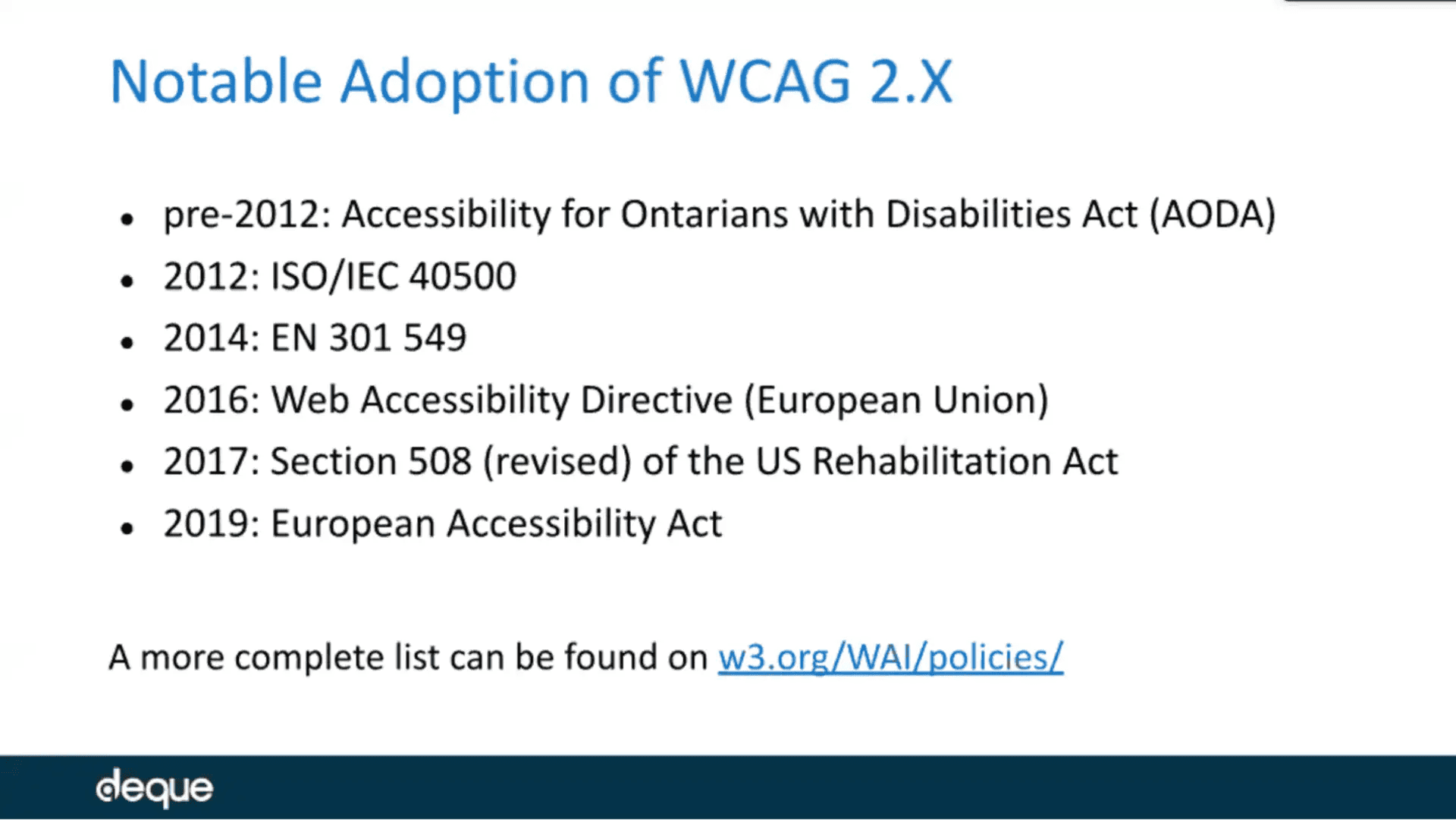

Caption: WCAG 2.2: An Overview of the New Accessibility Guidelines, Deque webinar. Notable adoption of WCAG 2.X

- pre-2012: Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act (AODA)

- 2012: ISO/IEC 40500

- 2014: EN 301 549

- 2016: Web Accessibility Directive (European Union)

- 2017: Section 508 (revised) of the US Rehabilitation Act

- 2019: European Accessibility Act

A more complete list can be found at w3.org/WAI/policies

In June 2025 the European Accessibility Act (EAA) will be enforced within the European Union member states. This directive also applies to e-commerce sites such as online stores. Not only websites inside the EU, but also websites that deliver goods or services to the EU need to be accessible.

Reputation and social responsibility

Another factor to consider given the above, and forthcoming, evidence is whether or not having a laissez-faire approach to accessibility would be damaging to your brand’s values and reputation.

The general public have dragged organisations through the dirt for far less than taking an indifferent approach to something as critical as digital accessibility. Let alone an approach that is downright discriminatory.

Aside from directly affecting your revenue and/or being liable to litigation, not prioritising accessibility could do irreparable damage to your organisation’s public image.

Modern consumers are savvy and selective about their brand associations and will prioritise relationships with organisations demonstrating corporate social responsibility.

Brands that parrot terms such as ‘inclusivity’ and ‘accessibility’ without backing this up through their products, services and processes will eventually find themselves held accountable to the consumer market.

A noble commitment to accessibility requires concerted effort and cannot simply be about paying lip service. Competition in the market dictates a high likelihood that the more brands giving serious consideration to accessibility the greater the chance of a domino effect which will raise the bar universally.

“You place your reputation at stake for not having a fully accessible digital presence. It negatively impacts your brand as a third of your users are disabled or know someone with a disability. These people lose respect for brands that do not prioritize providing equal web access to those with disabilities.”

ADA Site Compliance – " decoding="async" >

ADA Site Compliance – " decoding="async" > Truly accessible and inclusive human-centred design is about putting people first and leaving no individual behind, regardless of ‘protected characteristics’ like age, ability, gender, race, religion/belief, sex, sexual orientation or culture. Consider it your moral collective responsibility to prioritise accessibility as a business requirement because accessibility is a human right.

Quite simply: it’s the correct ethical choice and the right thing to do.

We’re all ‘disabled’

Yes, I know. I actually wrote that and what’s more I stand by it, as outlandish as it may seem. This is not to negate or minimise the daily challenges or impact of disabilities within a world that was not built for everyone equally.

But for the purposes of illustrating my argument: we are all ‘disabled’. At one time or another every individual is influenced by factors which affect their ability to access a digital platform.

“Disability is not just a health problem. It is a complex phenomenon, reflecting the interaction between features of a person’s body and features of the society in which he or she lives.”

World Health Organisation – " decoding="async" >

World Health Organisation – " decoding="async" > Everyone will experience disability at some point in their lives with increased likelihood as we age. Herein lies that pivotal Eureka! moment that changes your perspective on what digital accessibility means and how it affects all of your users. Conventionally when we talk about accessibility the majority of individuals will imagine a distinct minority group with permanent physical impairments.

The World Health Organisation encourages us to reframe disability not as a lack of ability or a personal health condition being the only cause of a barrier to usage, but as a ‘mismatched human interaction’. Human need is a spectrum and can’t be simplified with binary labels. So, what if I told you that we are all likely to experience temporary or situational mismatches on a monthly, weekly or even daily basis?

“A mismatched interaction between a person and their environment is a function of design. Change the environment, not the body. For people who design and develop technology, every choice we make either raises or lowers these barriers.”

Who Gets to Play? – " decoding="async" >

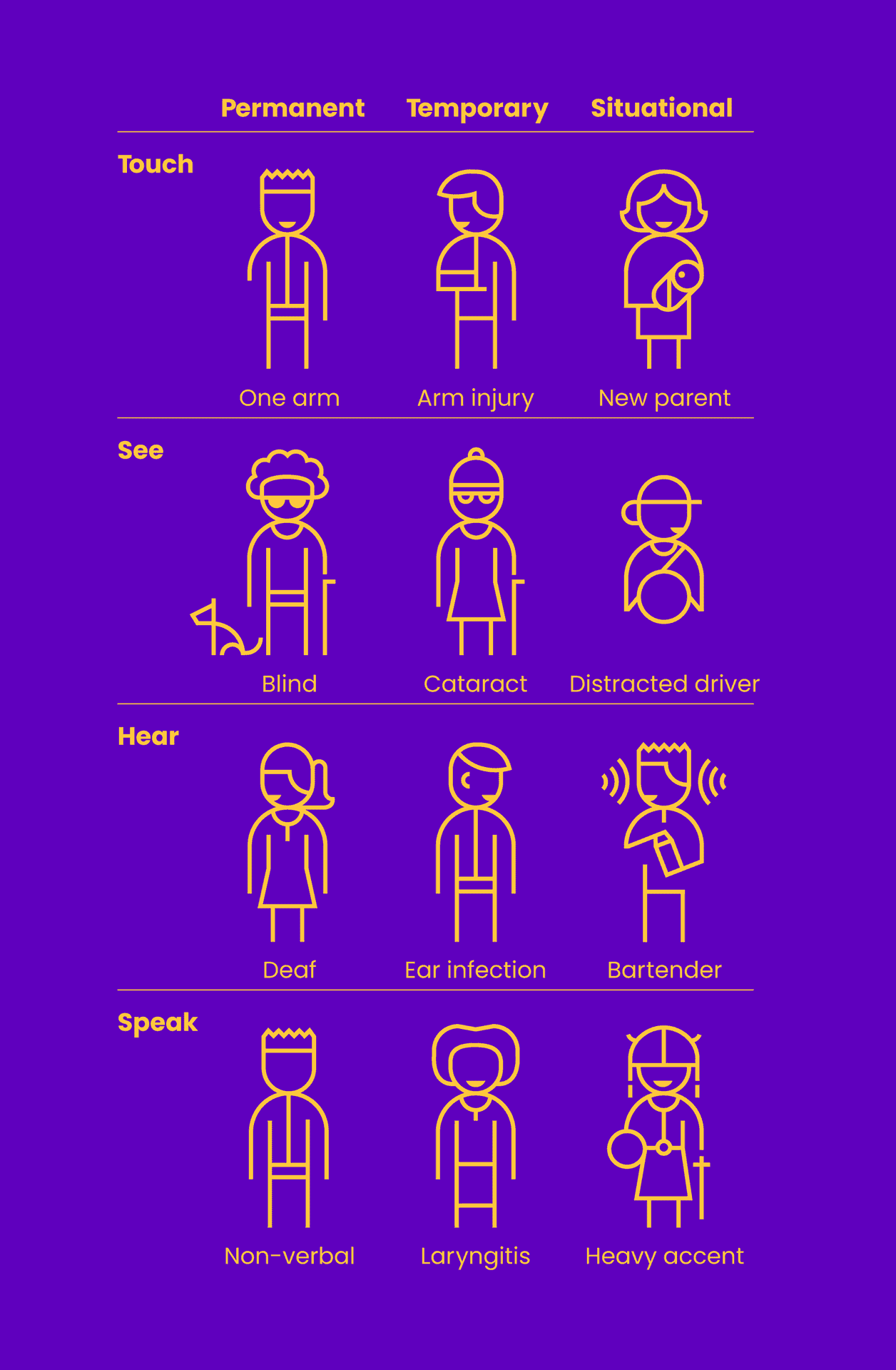

Who Gets to Play? – " decoding="async" > Consider the diagram from Microsoft’s Inclusive Design Manual. If we redefine how we think about Digital Accessibility then it allows us to develop empathetic human-centred solutions for a broader user base, and which all users can ultimately benefit from.

- Touch: permanent (one arm), temporary (arm injury), situational (new parent)

- See: permanent (blind), temporary (cataract), situational (distracted driver)

- Hear: permanent (deaf), temporary (ear infection), situational (bartender)

- Speak: permanent (non-verbal), temporary (laryngitis), situational (heavy accent)

Let’s break it down with some examples all related to the same sense, sight considering contexts that are;

- Permanent

- Temporary

- Situational

Permanent

These include permanent conditions that influence a user’s ability to interact with digital products. Perhaps your user has been born with this disability or it has developed over their lifespan.

Example: Willow was born without sight and therefore relies heavily on using screen-reader tools to access the web. These tools will read content aloud to her so that she can navigate through a website.

Solution: We ensure that the codebase has been tested thoroughly with screen-reader technology and that it is optimised to that effect.

Temporary

These include temporary afflictions or impairments which may affect a user anywhere in between a few hours to an extended period of time. Perhaps they have broken a bone or developed a migraine.

Example: Mohd has developed a migraine and this is affecting his ability to read the content of a web page. His vision is becoming increasingly blurred.

Solution: We ensure that sufficient colour contrast is used for all text content and that none of the content is sized below a certain threshold so that it is always legible.

Situational

These include situational or environmental factors affecting a user at that specific moment in time due to their surroundings.

Example: Sam is travelling on public transport and doesn’t have access to headphones but wishes to watch an informational video without disturbing other passengers.

Solution: Video content is transcribed and/or subtitled in order that all users are able to access the content regardless of their environment.

Making your website better for everyone

It’s also important to consider that in this context the term ‘disability’ can encompass a broad range of conditions from physical to mental, learning, emotional and cognitive.

Neuro-diversities such as ADHD, Dyslexia, Autism and Dyscalculia can also affect how a user interacts with a digital platform, but there is a disparity in these conditions being formally diagnosed and whether or not an individual self identifies with the disability label. Whilst there is a risk that these conditions could be overlooked when we talk about accessibility their inclusion in this conversation is vital.

There is a direct correlation between targeting accessibility and improved general usability that benefits all users. Able users are increasingly likely to expect familiar patterns of functionality from a digital experience, such as being able to tab through form inputs with their keyboard or use the escape key to close overlays/pop-ups.

Digital accessibility is not about serving a minority group, it’s about making your website better for everyone.

“A rising tide lifts all boats.”

If we endeavour to consider all three of the different contexts that may affect users when using a digital platform (permanent, temporary and situational) we can shift the understanding of what an accessible digital experience looks like.

If you want to further your understanding of these situations the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) provides a series of useful perspective video resources.

“Solve for one, extend to many. Everyone has abilities and limits. Creating products for people with permanent disabilities creates results that benefit everyone.”

Microsoft Inclusive Design – " decoding="async" >

Microsoft Inclusive Design – " decoding="async" > A (not so) silver bullet – beware of accessibility overlays

Digital accessibility overlays are marketed as a simple one-size-fits-all solution to accessibility compliance. Overlays are a broad term for technologies that aim to improve the accessibility of a website by applying third-party source code and artificial intelligence tools that patch over deficiencies in the front-end code of the website.

Overlay providers are also known to utilise native advertising and paid affiliate articles promoting their use, levy generalised criticism of overlays directly at competitors, purchase and falsify positive reviews, borrow credibility from accessibility experts, falsely advertise to promote their public image and litigate against critics. They also rely on a lack of public information around good accessibility practices and lean into their customer’s fear of litigation.

Overlays have even been known to manipulate page content to suppress detection of accessibility errors by auditing tools.

Limitations of overlays

In the last couple of years, an increasing number of lawsuits have been filed against businesses using overlays, in the US market, with some success. Potential customers of overlay services should also be aware of the limitations and pitfalls of these overlays in patching problems with front-end code.

Overlays are only capable of catching issues that can be identified programmatically, which is approximately 30% of the WCAG 2.1 success criteria. From there, AI can only apply ‘fixes’ to a subset of that 30%.

In addition to this, the ‘fixes’ made are automated without human evaluation, undocumented, and web operators can’t override the changes. Without human testing and oversight, it’s impossible to know if those changes actually make the experience accessible.

Overlays also do not resolve fundamental issues with inaccessible code and won’t fix a variety of different problems, including but not limited to;

- Missing headings or headings not being properly coded

- Missing alt text on images

- Link text marked clearly

- No labels on form fields

- Required form fields not indicated

- No submit button on form/no clear submit button label

Many of the above defects are fundamental to good coding and best practice (and are included in the list of common deficiencies).

Overlays may provide some tools which could prove useful to some users. However, there is compelling evidence from both digital accessibility professionals and users with accessibility needs that overlays will in many cases hinder their ability to navigate a website.

Users with genuine or distinct accessibility needs (such as those who require text to speech screen readers) will already have favoured assistive tools configured on their devices and simply require that the websites they are accessing have accessible design and code.

Further reading on accessibility overlays:

- Using an accessibility widget like accessiBe? You risk ADA litigation

- Siteimprove accessibiilty overlays

- Why accessibility overlays and widgets do not improve your website accessibility

- The death of accessibility overlays

- People with disabilities say this AI tool is making the web worse for them

- Do automated solutions like accessiBe make the web more accessible?

- Overlays don’t work

Common accessibility mistakes

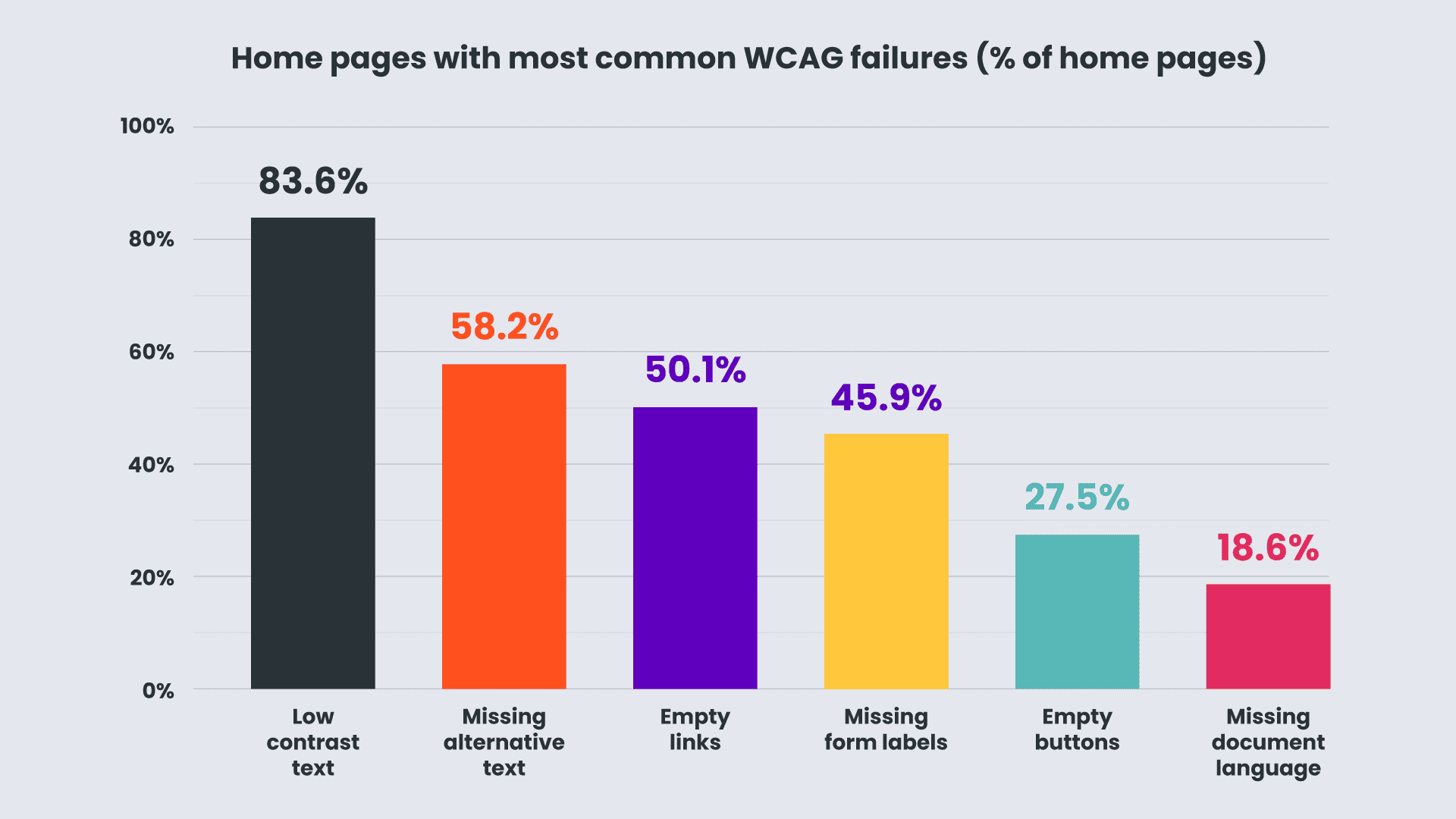

The WebAIM annual accessibility analysis of the top 1 million homepages shows that Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) errors are slowly increasing.

The 2023 analysis reveals that an average of 50 errors per homepage analysed were reported. Error density showed that 4.8% of all homepage elements had a detected accessibility error. This means that users with disabilities should expect to encounter errors on 1 in every 21 page elements with which they interact.

Overall 96.3% of all homepages analysed reported accessibility errors. This figure has only decreased by 1.5% in the last 4 years.

96.1% of all errors detected fall into six categories. These most common errors have been the same for the last 5 years. Addressing just these few types of issues would significantly improve accessibility across the entire web.

Caption: Home pages with most common WCAG failures (% of home pages)

- Low contrast text: 83.6%

- Missing ‘alt’ text for images: 58.2%

- Empty links: 50.1%

- Missing form input labels: 45.9%

- Empty buttons: 27.5%

- Missing document language: 18.6%

WebUsability provides a detailed breakdown of best practice for resolving low contrast text and missing ‘alt’ text specifically.

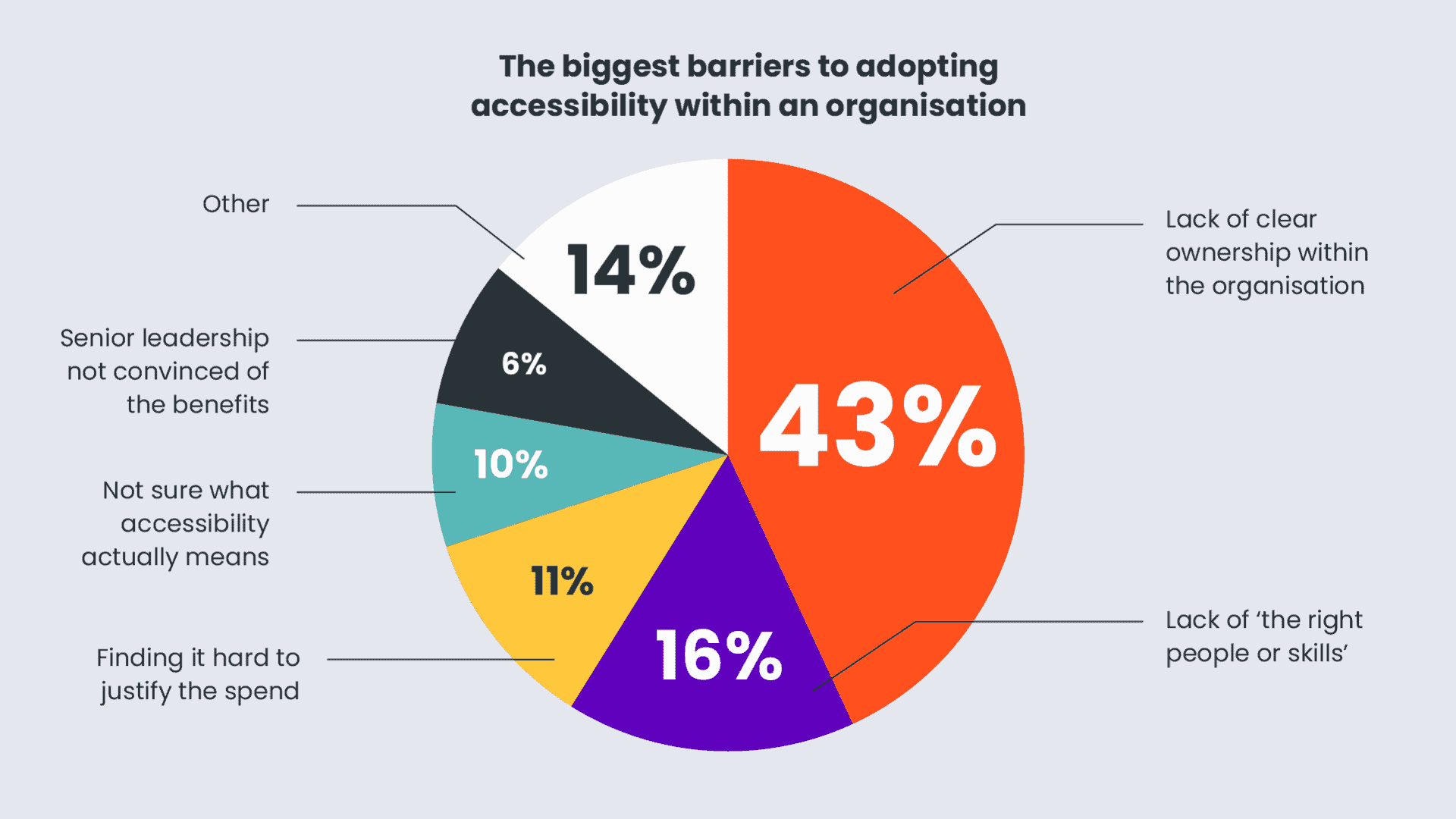

According to Inviqa’s report, Digital Accessibility: Achieving Great CX For All, the biggest barriers to adopting accessibility within an organisation include;

- Lack of clear ownership within the organisation: 43%

- Lack of ‘the right people or skills’: 16%

- Finding it hard to justify the spend: 11%

- Not sure what accessibility actually means: 10%

- Senior leadership not convinced of the benefits: 6%

- Other: 14%

Caption: The biggest barriers to adopting accessibility within an organisation

Many brands also hesitate to make their website accessible because they think they have to sacrifice aesthetics to create an accessible design. But this is far from the case.

“If your agency or designer says that accessibility will negatively impact your website in any way, then you need to find someone new to work with. Accessibility improves everything.”

What are accessibility overlays good for? – " decoding="async" >

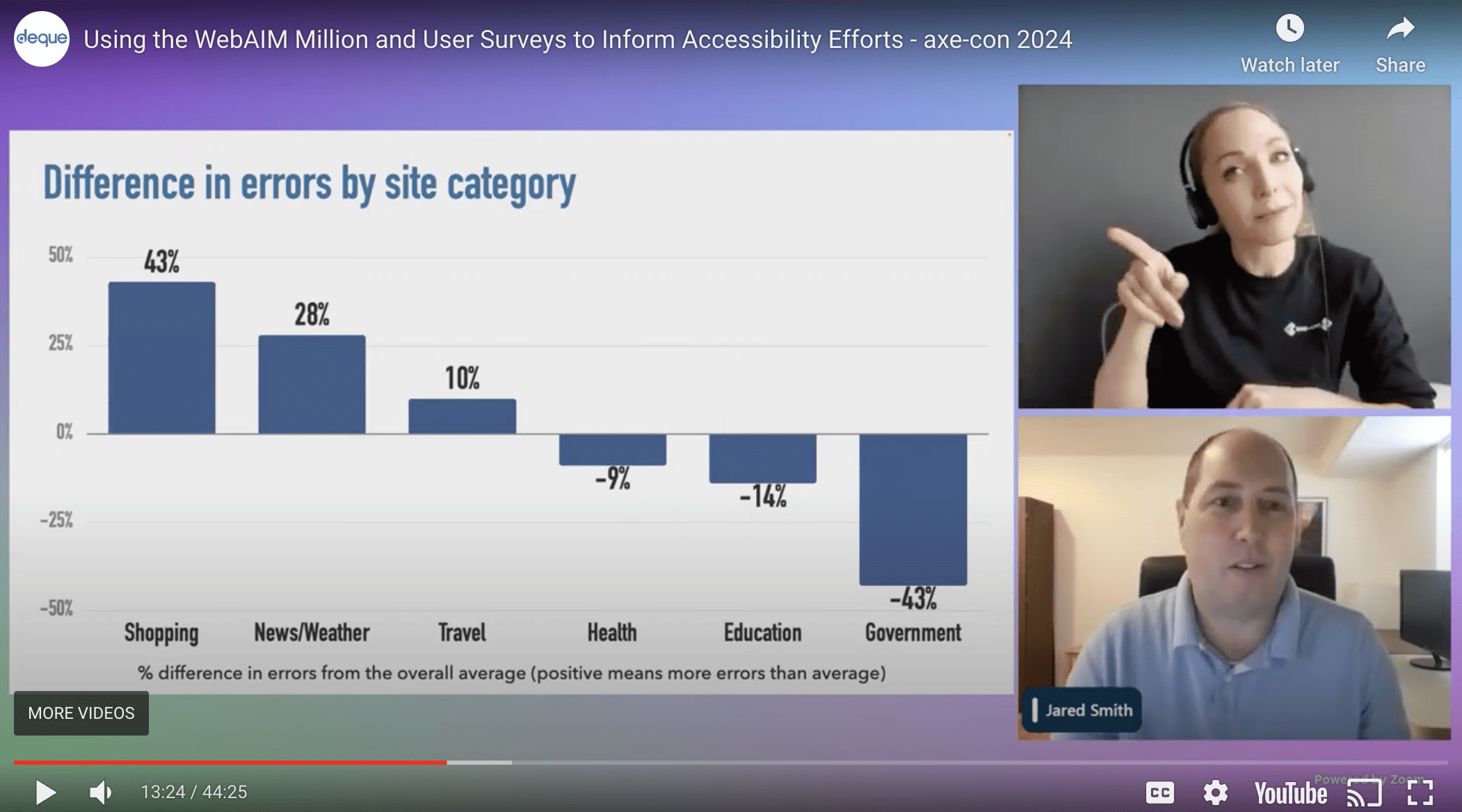

What are accessibility overlays good for? – " decoding="async" > WebAIM Million research presented by Jared Smith in his talk ‘Using the WebAIM Million and User Surveys to Inform Accessibility Efforts’ at axe-con 2024 also shows that eCommerce stores have 43% more accessibility errors than the average website.

Caption: Percentage difference in errors from the overall average (positive values mean more errors than average).

- Shopping +43%

- News/Weather +28%

- Travel +10%

- Health -9%

- Education -14%

- Government -43%

Compliance isn’t a checkbox

An independent organisation called the W3C Web Accessibility Initiative provides the definitive and globally recognised set of international standards for accessibility, known as the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG).

This framework is continually updated and versioned (2.0, 2.1 and 2.2), as well as being tiered at three levels of success criteria: A, AA and AAA. The success criteria are what determine ‘conformance’ to WCAG. The minimum standard expected of public services is AA compliance.

The guidelines are underpinned by four principles, which lay the foundation necessary for anyone to access and use web content:

- Percievable

- Operable

- Understandable

- Robust

Perceivable

Information and user interface components must be presentable to users in ways they can perceive.

This means that users must be able to perceive the information being presented. It can’t be invisible to all of their senses.

Operable

User interface components and navigation must be operable.

This means that users must be able to operate the interface. The interface cannot require interaction that a user cannot perform.

Understandable

Information and the operation of a user interface must be understandable.

This means that users must be able to understand the information as well as the operation of the user interface. The content or operation cannot be beyond their understanding.

Robust

Content must be robust enough that it can be interpreted reliably by a wide variety of user agents, including assistive technologies.

This means that users must be able to access the content as technologies advance. As technologies and user agents evolve, the content should remain accessible.

Make no bones about it, full compliance with the WCAG Success Criteria is a difficult target to achieve. This is particularly true if you’re working with an existing digital product which isn’t compliant.

But the important lesson here is not to let the perfect be the enemy of the good. It is better to try than not comply.

Access Guide provides a friendly and easy to understand introduction to the WCAG 2.1 success criteria, including example scenarios, rationale for importance and implementation instructions.

Accessibility compliance isn’t a one-time box-checking exercise, it requires an ongoing process of continuous review and improvement.

If you’re aware of accessibility deficiencies and working to make improvements then publishing an Accessibility statement that explains what actions you have taken, known issues that you plan to address and how users can provide feedback will help you to remain transparent about your ongoing journey.

The GOV UK Digital Service blog provides guidelines for writing such a statement. Both Scope and the Equality and Human Rights Commission demonstrate excellent examples.

A three-pronged approach

So whose responsibility is accessibility and how do you ensure your digital product is compliant? If you’ve made it all the way to the bottom of this article then, by now, you’re probably anticipating a magical key to unlock all of your accessibility problems.

The reality is that accessibility is a team effort. And as alluring as it may seem there isn’t a quick fix. Brilliant design or development alone won’t achieve compliance, transcending these barriers requires a shared product vision that all contributors can buy into.

There’s a big opportunity for those who are willing to make their services accessible. The following steps are essential on that journey:

- Integrate accessibility into your design and development processes from day one. If working with a pre-existing digital product then audit, improve and repeat

- Introduce user personas with accessibility requirements in order to validate and evaluate your decisions against a user’s needs

- Ensure everyone in your team is aware of their role in accessibility and acts on it

- Audit using the best digital tools available

- Test your digital product with assistive technology

- User test your digital product with people with accessibility needs

The British Standard 8878 summary provides a useful working methodology for managing digital accessibility.

Responsibilities

The three-pronged approach to accessibility sets out a unique set of responsibilities for Designers (accessible design), Developers (technical accessibility) and Content Editors (inclusive publishing) which includes:

Designer

- Familiar patterns adhering to best practice UX principles

- Typography System and legibility: words per line, line-height, font-size, use of case, paragraph spacing, typeface selection, letter-spacing, balanced text-wrapping, optimum legibility

- Layout; white-space, rhythm, visual hierarchy

- Consistent styling

- Colour contrast

- Minimum size touch/cursor targets and spacing for both handheld and desktop devices (see Ahmad Shadeed’s brilliant article on target sizes)

- Safe triangles

- Key interactive elements, such as the main navigation, within easy to reach Thumb Zones

- Clear interaction feedback states for interactive elements (:hover, :active and :focus)

- Hyperlinks underlined and contrasting sufficiently with content

- Accessible forms and validation

- Overflow interactions

- Information scalability (0, 1, 2, 1000, error)

- Labelled iconography

- Removed reliance on carousels

Developer

- Correct use of semantic HTML

- Sequential headings

- Landmarks

- Use aria-attributes where necessary to inform screen reader users of the same information as visual users

- Progressive enhancements

- Screen reader only content

- Keyboard navigation, tab stops and :focus states (including ESC key events)

- Skip links

- Dynamic units and zoomable content

- Focus trapping

- Mark-up for prefers-reduced-motion preferences

- Sequential order of :focus elements in the Document Object Model (DOM) for keyboard navigation

This video from Microsoft Enable does a really great job of explaining the benefits of accessibility friendly code mark-up in a simple and engaging manner.

Content Editor / Site Admin (often client side)

- Clear content/language

- Alt tagging of images including correct level of context

- All live text (no content flattened into imagery)

- Transcriptions of video/audio content

- Heading tags used in hierarchical order

- Information presented clearly using the components available from the Design System to avoid cognitive overload

- Descriptive link text

The right tools for the job

When it comes to accessibility testing the digital market is flooded with automated tools that can test for accessibility deficiencies. But it’s important to note that these tools have limitations and can only report on approximately 60% of issues. It’s therefore crucial to take a multifaceted approach to testing:

- Use automated tools such as WAVE or AXE to report approximately 60% of accessibility issues

- Some tools on the market, including AXE, help you perform Intelligent Guided Tests (IGT) manually to bring that number to 80%

- Testing manually using assistive technologies will bring that number much closer to 100%. This includes native operating system configuration and third-party tools. Users may implement these to enhance their digital experience, such as screen-readers

- The final step is to test directly with users in order to validate and evaluate any changes

Conclusion

If there’s one thing that GCSE English taught me, it’s that no essay is complete without a final conclusion. In this case the take home is a pretty simple question: given all of the above, can you afford to not take digital accessibility seriously?